South Africa's white paper on remand detention management finalised

The purpose of the White Paper on Remand Detention Management is to "communicate the principles driving the management of 'all categories of un-sentenced persons in DCS facilities ... (and) awaiting further action by a court'. Among the principles informing the White Paper is that the purpose of remand detention is not to penalise or punish, but to ensure due process in the court of law at which the detainee is to be tried. In such circumstances, minimal limitation of an individual's basic human rights is obligatory "while ensuring secure and safe custody".

These rights, according to the White Paper, include uninterrupted medical care throughout the custody process where necessary; access to family and friends; adequate legal advice in preparing for trial; and appropriate treatment in situations of vulnerability (including terminal illness, pregnancy and when a mother is detained with a child). With this in mind, the White Paper points to the fundamental importance of correctly classifying remand detainees in order to ensure that time spent in custody is managed appropriately.

The White Paper is necessary because the Correctional Matters Amendment Act 5 of 2011 (the Act) provides for the incarceration of “remand detainees” in a “remand detention facility” in contradistinction to the incarceration of sentenced “offenders”. The Act provides that remand detainees may be subjected only to those restrictions necessary for the maintenance of security and good order in the remand detention facility and must, where practicable, be allowed all the amenities to which they could have access outside the remand detention facility.[1] The amenities available to remand detainees may however be restricted for disciplinary purposes, and may be prescribed by regulation.[2] Special provisions in the Act apply to pregnant, disabled, mentally ill, terminally ill or incapacitated, and aged remand detainees.

The Act provides that if there is no correctional centre or remand detention facility in a district an inmate may be detained in a police cell but not for a period longer than seven days. Further, no remand detainee may be surrendered to the South African Police Service for the purpose of further investigation without authorisation by the National Commissioner.[3]

The Act has certain provisions regarding the time periods for which remand detainees may be held, which although enacted, have not yet been promulgated by the President.[4] Once promulgated these will limit pre-trial incarceration to two years after initial admission, “without such matter having been brought before the attention of the court.”[5] South African remand detention facilities will be required to notify the National Prosecuting Authority twice a year about cases involving remand detainees who have been held for successive six-month periods. When individuals continue to be detained after two years, their cases must be referred to court for annual review.

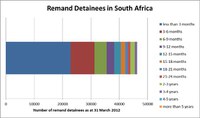

As at 31 March 2012, there were 2470 remand detainees in all correctional centres in South Africa who had already been held for more than two years, according to the2011/12 Annual Report of the Inspecting Judge of Correctional Services. This means that 1 in 20 of all unsentenced inmates as at 31 March 2012 had already been held for more than two years. Once the legislation is promulgated, all of these detainees’ cases will have to be referred to court for review. Similarly as many as 23 546 or 32% of all unsentenced inmates as at 31 March 2012 had already been held for six months or more, according to the 2011/12 Annual Report of the Inspecting Judge of Correctional Services.

Although the White Paper acknowledges these time-limit provisions of the Act, there does not appear to be any detail as to the mechanism of implementation in the White Paper. A round table to discuss Remand Detention is to be hosted by CSPRI on 23 May in Cape Town. Officials from the Department's Remand Detention Management Unit will be in attendance.

[1] Section 9 Correctional Matters Amendment Act 5 of 2011, which amends s46 of the Principal Act

[2] Section 9 Correctional Matters Amendment Act 5 of 2011, which amends s46 of the Principal Act

[3] Section 9 Correctional Matters Amendment Act 5 of 2011, which amends s49F of the Principal Act

[4]Regulation Gazette No 35093 of 01-March-2012, Volume 561 No 9698, which determines 1 March 2012 as the date on which the Correctional Matters Amendment Act 5 of 2011 comes into operation, except for section which only comes into operation in respect of the amendments made to sections 46,47,49,49A,49B,49C, 49D and 49F of the Principal Act.

[5] Section 9 Correctional Services Amendment Act 5 of 2011, which amends s49G of the Principal Act